Seattle Weekly

Chuck Amok

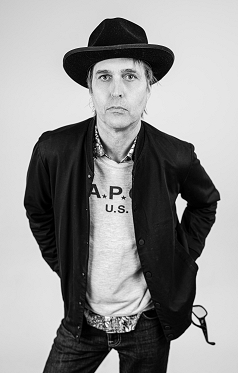

Probably best known—“if at all,” as he jokes—as the white-hot guitar slinger for ‘80s Paisley Underground turned alt-country avatars Green on Red, Chuck Prophet finally seems to be carving his own niche in the rock world after 20 years of scuffling. With a résumé that boasts collaborations with everyone from Cake to Kelly Willis and a string of exceptional albums under his belt, Prophet’s name is begging to be uttered in the same breath as a cult of similarly styled, soulful storytellers: Dan Penn, Ry Cooder, and his spiritual mentor, Jim Dickinson.

Beginning his solo career at the dawn of the ‘90s with the country quaint Brother Aldo—a modest collection of late-night demos made for just a few hundred dollars—Prophet spent the next decade recording a succession of accomplished platters that won him acclaim throughout Europe but earned little attention in America. His stateside profile finally received a much-deserved boost with the release of 2000’s The Hurting Business—a stirring mélange of new technology and old soul that earned raves across both continents. This year’s equally ambitious follow-up, No Other Love, has pushed his burgeoning popularity even further, spawning a single, “Summertime Thing,” that landed in the upper reaches of the AAA charts.

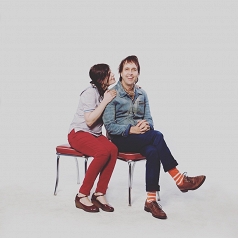

On the eve of his two-night Seattle stand, we caught up with the always engaging Prophet on the road in Minnesota, in the midst of a tour with the Mission Express—his crack backing band featuring wife Stephanie Finch (see main story) and longtime Bob Dylan drummer Winston Watson. A gifted raconteur and doyen of deadpan, Prophet weighs in on a variety of topics, from his long overdue success, to working with Warren Zevon, to his envy of Keith Richards’ appendage.

Seattle Weekly: So the last time we spoke back in June you were getting your first bit of real exposure with “Summertime Thing”—which ended up becoming something of a hit.

Chuck Prophet: Yeah, it’s been a weird summer, man. David Lee Roth and Sammy Hagar made peace, Chuck Prophet had a song on the radio after 20 years in the business, . . . and we’re going to war. You know, it always comes in threes.

Have you seen any change in the audiences at shows because of the airplay?

Yeah, I’d have to say it’s had a profound effect on things. There seems to be an increase in the ratio of shapely young ladies to men with beards down in front. Of course, nobody’s complaining about that—not even my wife.

I mean, it’s just exciting for me to have my skinny foot in the door of pop culture. It’s such a little sliver, but to go into, say, a supermarket like Whole Foods—or as we in the band like to call it, Whole Paycheck—and hear my voice coming out of the speaker above the salad bar, it’s a total thrill.

You’ve also got your first big national TV appearance coming up (Oct. 8, on CBS’ Late Late Show with Craig Kilborn).

Yeah, we just confirmed that. That’s sent everybody in the camp here into a whirlwind of activity. Everybody’s arguing about what they’re going to wear. So it’s chaos. We’re actually gonna play the second single: the song with the uncompromisingly long title of “I Bow Down and Pray to Every Woman I See.” Hallelujah!

Speaking of women, in addition to your wife, you’ve had great working relationships with a number of female artists—Kelly Willis, Kim Richey, and Lucinda Williams, who you recently opened a tour for.

Yeah, it would be impossible for us to even invent a better tour to be part of. Lucinda’s got such a great audience, a really astute audience. And also, there’s some kind of mysterious, magnetic, charismatic thing to Lucinda. It was just a joy to watch her every night. It was like going to church. Or going to school. Or both.

It’s a weird coincidence but I was planning to ask you about working with Warren Zevon (Prophet played guitar on Zevon’s 2000 album Life’ll Kill Ya) and then news just came out that he has a terminal case of lung cancer.

I heard about it yesterday. (Long pause). I . . . I don’t . . . words kinda fail me on that.

Working with him, though, he was intimidating in so many ways, but also astonishingly intelligent. It was just incredible to be around him. [laughs] He must’ve drank about a case of Mountain Dew a day—and you didn’t want to be around when he ran out.

He really is one of the sharpest, funniest, wittiest people I’ve ever been around, and he truly intimidated the dog shit out of me. I tried to just kinda of blend into the wall when we were in the studio. But as acerbic as he is and as surly as he can be, he’s also one of the sweetest guys, too. I don’t know . . . it’s tragic.

He’s also a guy who didn’t lose his edge when he had a taste of success. Obviously, yours is on a much more modest level, but has the relative success you’ve enjoyed with the last two albums changed the way you approach things at all?

It’s taught me to follow my instincts. Because the way I’ve been making the last couple of records . . . I didn’t go in with any expectations. More and more, I’ve found people who let me make my records—for better or for worse—and there’s been very little meddling by anybody in the process. And I think that meddling has really fucked me up in the past.

But there must be some pressure on you as you look to write the next record?

It’s funny, Dan Penn said that after he got his first song cut, he was never ever really happy from that moment on. He said, “I might be out swimming or waterskiing or on a boat somewhere, but I’m never really quite happy unless I’m in the process of wrestling a slick idea to the ground.” And that’s kinda what songwriting is all about. For me, as much as this [new] record has made a little bit of noise, you’d think it should give me some confidence. But the reality is, I’m such a superstitious, neurotic, irrational motherfucker that now I’ve got this constant low-level anxiety of “Where’s the next one coming from?” [laughs]

And I hear people like Keith Richards do interviews and say [copping an English accent], “It’s like you put up your antenna and the songs just come to you, man.” And, I’m like “Damn, I gotta get one of those antennas.”

by

Bob Mehr

on

December 31, 2003

Pulse of the twin cities

Building on the hippety-hoppy, funked-out, rocked up, smoothed-down grooves of his last knock-out release, No Other Love, Prophet and “long-suffering wife/bandmate” Stephanie Finch (along with keyboardist Jason Borger, Red Meat alum/pedal steel whiz Max Butler, four bassists, five drummers, a beatbox and a programmer) gleefully continue to break all the rules here.

The lyrics at first seem deceptively simple-straight-forward love songs or story-songs or thematic current event songs or dark, cosmic-surfer songs-but upon closer listen, one finds Prophet to be among the rarest of song-writing talents: One who’s able to meld the sage observations of the omnipotent Outsider with the painful, all-too-human declarations of what he calls “... the smallest man in the world ...” to create tunes that let the listener both peer anonomously into fascinating tales and simultaneously experience the emotions of the subjects thereof.

He probably nails his own wonderfully twisted psyche and gloriously original oeuvre best in his own words: “All roads lead to Dylan I suppose, beyond that, if I mention one influence I’d have to leave out a hundred. One definite influence on this record is my increasingly acute awareness that we’re living in the modern age. Don’t get me wrong; I’m not about to throw my laptop into the river any day soon. I’d probably end up developing some kind of a tic without it. There’s just no time. No time to daydream, even less time to think. Fast food express lines, meth?paced TV, medications marketed to women who ‘have no time for yeast infections’ (as if the rest of us have the time). Genetically cloning the family pet, prescription miracle drugs, mad cows, madder scientists ... watch those carbs! The psychosis! On second thought, I wouldn’t have it any other way.” Neither would we, Chuck. Neither would we.

December 31, 2003

San Francisco Reader

Light Finally Shines on Chuck Prophet

There’s been lots of water under the bridge since Chuck Prophet’s band Green On Red tried to take the airwaves by storm in the 1980s. They wrote the right songs, had the right look, and performed a kick-ass live show. Big record labels rolled out the red carpet and extended Big Time contracts. But things just never panned out. Chuck quit the band, cleaned up his act, and throughout the ‘90s released critically-acclaimed, slim-selling CDs. But suddenly, Chuck Prophet’s on the radio. “Summertime Thing” is a hit, and finally, finally, America’s getting a taste of the genius of Chuck Prophet.

Jeff Troiano: What’s happening, Chuck?

Chuck Prophet: Not much shaking here. I finally resurfaced after about six months of submarine duty.

How long have you been home?

I guess for about a week. I went to Nashville and did some work after the tour ended.

How do you like that Nashville scene these days?

Well, I dig it, you know, because for me as a writer, well, for a number of reasons. I don’t really party anymore, so that’s what’s left of my social life-writing with other people. And Nashville is the last vestige of any sort of Brill Building spirit.

What kind of building?

The Brill Building was a place in New York where Carole King and Doc Palmis and Gerry Goffen wrote songs. If you got lucky, somebody might record one.

You’ve had some luck in that regard lately. Who’s been cutting your tunes?

Well, I’ve had a bunch of obscure records over the years, but last year I did have a top-40 single by a girl named Cyndi Thomson. It caught on. Cyndi’s a nice Christian girl, farm-fed, centerfold material. My friend Kim Richey and I wrote a song called “I’m Gone,” actually upstairs from the Red Vic on Haight Street. It’s kind of a ‘60s Tommy James kind of song. We made this real ghetto demo of it in this crappy studio with a cement floor, and we played it and cut it and put a few things on it, and we decided it needed bongos, and a year later it comes out on the Cyndi Thomson record-with bongos.

So they stayed true to the Haight Street feel?

Getting a song cut, even if the version strays off from what you had envisioned, is amazing. There’s no such thing as a bad cover version of a song. It’s a good day.

How do you get compensated when someone else makes a hit out of your song? Is that big money?

Well, yeah, there’s sort of a bittersweet ending to that story that I’m not going to bore you with, as far as making bad business decisions. On a record like that, you should make some change. You get compensated for every time it’s sold; you get your pennies for every time it’s played on the radio. It’s all gravy.

The reviews have been very positive for your new CD, “No Other Love.” How’s it selling?

This record was pretty rare. There was probably less blood on the floor after we finished this one than any of the others. We caught a little bit of a wave with the single on the radio. And for so many years we had just ignored North America, hoping it would just go away. Not that we were selling out stadiums or ballrooms across Europe, but Europe has always been good to us. Our single has allowed us to infiltrate pop culture, just a skinny little foot in the door. I heard it coming out of a little speaker in a salad bar in Philadelphia, which was rather cool. That helped a lot. And Lucinda Williams took us out on tour all summer; that really helped with record sales.

How did that happen with Lucinda?

My A&R guy, Peter Jasperson, is an old friend of hers. He played the record for her, she liked what she heard, looked up and said, “Do you think he’d come out on tour with me?” That was it.

How many shows did you do with her?

It might have been 20-some odd dates with her. She only plays three or four times a week, so we were out there for a couple of months in the Midwest and the East Coast.

What did you do with all of that downtime on the road?

We did everything we could do to keep up with her two buses. I tell ya’, man, I mean sometimes there might be 800 miles between gigs, and I have an ‘88 Dodge Ram, so we spent a lot of time sucking her diesel, as they say. But the highlight of the whole thing for me was when we had this show at an amphitheater, and the weather was beautiful, and these beach balls were bouncing everywhere. Lucinda just kept looking at these things while she singing like a puppy, and she said, “Heck, I don’t know. It’s a summertime thing.” But there were many nights when we’d play the gigs and we’d gather around the catering, and we’d have an official band meeting, and we’d say, “Okay, tonight, after we finish our set let’s load up the van, get the union guys to help, and get the fuck out of here, and try to get in four hours tonight. So we’d make the grandiose plans and then, inevitably, when the time arrived, I’d look around for everybody and they’d be glued to the side of the stage watching Lucinda’s first encore. Night after night, watching Lucinda is like going to church or going to school or both.

You tasted success in the past, during the Green On Red days. Did you ever have the big tour bus?

There were times. I mean, somebody else was paying for it. Yeah, we tasted success, but we were always well under the radar. We had a couple of major deals with labels, but we were always kind of stowaways for those labels. Eventually they’d have a board meeting and say, “Who the fuck are these guys?”

The new stuff seems to have lots of interesting influences. I hear a bit of hip-hop, some Middle Eastern, some sampling, and of course the roots-based stuff. How’d that happen?

As a songwriter, I’m a slave to traditional song craft, whatever I do. I mean, my heroes are still going to be Dylan and Carole King and Hank Williams. But for me, the process of making new records is a matter of constantly seeking new ways to cast the movie. I’m turned on by people like Moby and DJ Shadow, and I appreciate what those guys have been able to do by bending traditional song structures. As much as I admire that stuff, I’m still a “first verse, first chorus” kind of guy. I see some people out there taking some sort of modern approach and trying to shoehorn it into their songs, but that doesn’t really work. You’ve got to listen to the song’s needs and go with that.

How do you categorize your sound these days?

What I do is “American” music. You might call it “Americana.” I just do what I do, throw in what interests me, what I gravitate toward, throw it into a pot, bring it to a boil, and I see what floats to the top. The European tradition of music is that you play music as it’s written on the page; I’m not part of that tradition.

Which radio stations are playing “Summertime Thing”? What do you call that format?

There’s a format called AAA-WXRT in Chicago; KFOG here in San Francisco; there are a lot of them, kind of like KFOG. KFOG has had an incredibly profound affect on the things here at Chuck Prophet, Inc. I mean, I’ve got my ‘88 Dodge Ram van with 250,000 miles on it; I’ve got a five-piece band; I’ve got a drummer with a teenage daughter, and radio has really helped. I’d heard about good things like this happening, and I’d read about it. It’s just wonderful.

I heard something about a national TV appearance…

We did the Craig Kilborn Show. It was pretty exciting, pretty nerve-wracking. We had a rehearsal to set the camera moves and stuff, and you play it once through for the audience and that’s it. It was cool. Craig is not at his best when you’re playing, but I kept pointing over there and yelling at him, “Yo, Craigy, ‘I bow down and pray to every woman I see. Can you feel me?’” So that was sort of my inside joke. But he was pretty cool. He tracked me down into my dressing room and said, “I’m hearing a little Iggy Pop in there.” And I said, “Yeah.” And he said, “I’m hearing a little bit of Dylan, a little Beck,” and I said, “Yeah, yeah, yeah.”

Who are you listening to these days?

“Leonard Cohen’s Greatest Hits;” David Holmes’ Organization; I like the new Cornershop record. I like a little bit of the new Dixie Chicks’ record. I listen to a lot of old music and as much new stuff as I can. When it comes to songwriters, it’s still Warren Zevon, John Prine, and Randy Newman for me.

What’s it like doing what you do from here in San Francisco? Is it awkward sometimes? I mean, do you ever want to be in L.A. or living in Nashville?

No, I love it here. There’s just something in the air here. It sounds kind of corny, but there’s just a certain spirit and a certain quality to the light that I love. I moved here to go to college, and it has just always seemed like a place where people were waving their freak flags high. I’ve always been able to find a place to play and to work with some great musicians. And it’s not an industry town; it’s a town for freaks.

Who would you recommend that we listen to locally these days?

There’s a guy in the Mission from Detroit, Kelly Stoltz. We played a gig with him, and he gave me a vinyl record that he’d recorded on his 8-track. It’s probably one of the most beautiful things I’ve heard-that I can ever remember hearing. I’m all for Kelly Stoltz.

I’m going to throw a few names at you. In 10 words or less, tell me what you think. Here’s the first one: Eminem.

Stone cold genius.

Joe Henry.

Madonna’s brother-in-law.

Ryan Adams.

He’s just an exceptionally talented puke.

Britney Spears.

No redemption there.

Bruce Robison.

Oh, writer of perhaps the best song to come out in 2002-“Traveling Soldier”-as covered by the Dixie Chicks. If it doesn’t bring tears to your eyes, then just check yourself for a pulse.

Gram Parsons.

Beyond country rock; beyond rehab.

And last but not least, Mr. Bob Seger.

Vastly underrated.

Kelly Willis made the following quote about you: “If I could sing like anyone, I’d sing like Chuck Prophet.” What do you think of that?

She was confused but I’m not gonna call her on it.

Do you care what anyone else thinks about your music?

I can’t afford to care too much. I had a conversation with a friend the other who said, “Well, I guess everybody’s happy now, now that the record’s doing well.” What do I fucking care? I’d never get anything done. And that’s the kiss of death to start to care too much. Don’t get me wrong-I want the love. But I don’t wanna have to work to hard for it.

by

Jeff Troiano

on

December 31, 2002

All Music Guide

Prophet’s follow-up to The Hurting Business finds him in excellent form, still making American roots music but casting his net a little wider to bring in a few more influences. For example, “Elouise” kicks off with a rhythm straight out of the Rolling Stones’ “Sympathy for the Devil” before evolving into something looser and less threatening, and “Summertime Thing” has the laid-back vibe of the Young Rascals’ “Groovin’” welded to some funky wah-wah guitar influenced by the Isley Brothers. With a voice suggesting that he’s training to be Tom Waits when he grows older and occasional lyrics (as in “Run Primo Run”) inspired by the vintage Dylan songbook (the Farfisa organ that recurs in the album only furthers the connection), there’s a strong romantic streak running through his work, most evident in “No Other Love” and even the growing-older wisdom of “Old Friends.” His songwriting continues to grow and his guitar skills (which he tends to hide under a bushel a little), never flashy or grabbing the spotlight, have become mature and sophisticated, a long way from his days in Green on Red. One of America’s great underground artists, Prophet’s slowly blooming into a major figure.

by

Chris Nickson

on

November 11, 2002

The Rage

New Traditionalist

Chuck Prophet may be best described as a new traditionalist - or a traditionalist for the 21st century. He works happily within the constructs of American roots music’s structures and sounds, but sets them on their ears with clanking, roiling rhythm sections and lyrics that sketch images in bold outline but leave the details blurry. With his considerable guitar skills, murky grooves and growling delivery, Prophet can twist a conventional song into a gritty, hungover animal that will let you pet it, but may bite your hand off if you ain’t careful. The artist who cut his teeth as guitarist for Green on Red in the ‘80s has grown, over the past decade, into a formidable writer with a distinct vision. As he tells The Rage, ‘The challenge is that you want songs to make sense, you just don’t want ‘em to make too much sense. So, there’s a slightly abstract expressionist approach to it.’

And expressionist he is on his sixth and most recent solo release, No Other Love. With 11 snarling, swooning songs and a no-b.s. delivery, Prophet is at his finest. The sonic corners of the record are filled (but not overstuffed) with wonderfully skewed details - tape recorders, omnichords and accordions peer out from the shadows. ‘For me,’ Prophet explains, ‘records are defined by things like the theremin at the beginning of Good Vibrations or the fuzz guitar on Satisfaction or the fact that somebody was smart enough to tell Roger Daltrey to stutter when he sang My Generation. Those are the little things.’ Laughing, he adds, ‘Sometimes they just appear, other times you gotta go around with a flashlight in the dark looking for them.’

With his gruff delivery calling to mind Greg Brown and hinting at Tom Waits, Prophet’s lyrics are especially effective. At his most tender, Prophet still comes off rough and ready. He also shares much in common with Lucinda Williams, for whom he opens at the debut Miller Lite Uptown Mix on Wednesday, July 3. Both artists manage to be simultaneously conversational and otherworldly in phrasing and in lyrical content. As Prophet explains, ‘I’m a traditionalist at heart in terms of songwriting. I’m a verse/chorus/verse/chorus kind of guy. The challenge for me has always been finding new ways to turn it sideways. My songwriting heroes are still gonna be Carole King, Dan Penn, Hank Williams. But it’s interesting, in a lot of modern music like DJ Shadow or even Moby, how they’ve sort of thrown a lot of traditional structure out the window. I like that from a distance, but I guess that’s the challenge, to find ways to turn verse/chorus/verse/chorus/bridge inside out a little.’

Although Prophet consistently overcomes that challenge, it’s not always easy. ‘For me, right around the middle of [making] the record I feel like one of those Goya etchings with bats coming out of my head. This record was no different. Individual songs ... some of them are more stubborn than others. Some, you try to wrestle to the ground and they end up wrestling you to the ground. Some come on the first take, and others you gotta put them up on blocks and rotate the tires and you gotta cut them 10 times.’

Now the songs that compose No Other Love are back off the blocks and on the road, which is where Prophet, partner and collaborator Stephanie Finch and Prophet’s exceptional band pretty much stay. That’s the strategy for the year, Prophet says. ‘The plan is to go out and play and see where it takes us. Play every last f—king burg and city that’ll have us, and most of ‘em twice.’

by

Clay Steakley

on

July 5, 2002

Release Info: Hurting business

Martin Goldschmidt from Cooking Vinyl called and asked Chuck to make another record. He didn’t have to ask twice, though he did have to wait a while.

“After I finished the last record naturally I was looking forward to going out and kicking the songs around on stage until each and every one of them learned how to entertain itself” explained Prophet. “Some songs never did learn how to behave… Eventually I started collecting new ideas. That inevitably led to a shoe box full of cassettes, pieces of string, titles, grooming tips, etc. In the cold light of day, some grooming tips are better than others. But before I knew it, some of these fragments disappeared inside full-blown songs. The rest was long sessions of work—taking the Farfisa in for repair, rewriting changing keys, sneaking looks at the rhyming dictionary when hopefully no one was looking—all the stuff that should never see the light of day”

Jacquire King (a neighbor of Chucks who worked on Tom Waits’ Mule Variations among too many other cool things to mention) was enlisted to co-produce and re-produce. “Jacquire has a background in everything from hip-hop to field recordings,” says Prophet. “I’m familiar enough with the two guitars/bass/drums terrain, so I played him some of my four track sketches. To my surprise he encouraged me to run with those scrappy parts of songs. In fact, we dumped a lot of the skeleton tracks into the computer. I’ve always needed someone on the other side of the glass that I can trust Having a co-producer enables me to avoid going off into too many secretarial tangents such as, ‘Are there enough tracks left to cover the Bullfight scene; Is there a mic on the baby rattler?”

Prophet continues, “The last record was like a play. Five of us on our fret at all times, playing simultaneously into the -tape recorder. This one was more like a movie: The players were assembled (the usual repeat offenders and some blind dates); there was no pre-production or rehearsals. Tracks were recorded and dissolved into opposing song locations. Bridges were reconstructed from fragments of dream sequences. All the different “shoots” came together in the editing room—a little like a ‘70s B movie—except we’ve got computers that can do that now!”

Between records Prophet is routinely drafted into other projects. “For all the right and wrong reasons; Just like everyone else I need to pay the utility bills.” He lent sideways guitar riffing to the most recent certified gold record by Cake as well as to Kelly Willis’ critical favorite, What I Deserve, among other more or less notables. He also took a few trips to Nashville to immerse himself in the world of veteran songwriters. “I’ve gone so far out of my~y way to avoid doing things professionally for so long Nashville was a romantic change of scenery It’s a kick to see how others do it. Sometimes it’s easy, sometimes it’s like a bad date. Sometimes “it ” pays off” Kelly Willis recorded the Dan Penn/Prophet composition, “Got A Feeling For Ya.” There were also Prophet songs and c~writes on records from artists diverse as Kim Richey and Penelope Houston to Jake Andrews and others. He also contributed the track “February Morning” to an upcoming Kosovo relief benefit CD on Twah Records. Before heading out on the road in support of The Hurting Business, he’ll stop at Ft. Apache in Boston with producers Sean Slade and Paul Kolderie to work on the new Warren Zevon record.

May 31, 2002

Track By Track: The Hurting Business

Rise

At first it was called ‘A Change Is Gonna Come’, but you haven’t been able to call a song that for several hundred years. That’s Stephie Finch cast in the role of the wayward child. It’s a little like Tony Joe White piggybacked over a Turtles breakbeat or a trip from San Francisco to San Antonio in less than three minutes.

The Hurting Business

Mike Tyson said it first. Presumably, he meant it literally. Biting off years and breaking hearts is all in day’s work for some showfolk. I think I was under the influence of ? and the Mysterians and Sir Douglas Quintet at the time. Maybe Jerry Springer will pick up on it as a theme song. It’s all in there.

Apology

Randy Newman meets Glen Campbell in a wine bar and they start arguing about the south. In comes El Vez, who neither one has ever heard of; a young lady on each arm and a spare bringing up the rear. All of them seem to know exactly who he is. He introduces himself and Randy opines, “You’re not even the king of bottled beers where I come from.” Things get unprofessional. Before it’s all over, everybody wants an apology. Sensitive to insensitive and back again. Conn organ metronome “count off’ preserved on cassette and reproduced by Jacquire King.

It Won’t Be Long

Trailer park trash, carpetbaggers with high Arbitron ratings. The sad beauty of freak encounters recollected, last chances cheerfully blown, Waterloo sunsets digitally altered by faceless electromagnetic collectives. Put your Business in the street and the heartland takes a bow. Jenny Jones nightmare appearance hangover recounted in three verses.

Shore Patrol

Old movies. Anti-heroes. A tribute to Jack, Hal and the generation who took Hollywood by the balls and held firm for a while. Not nearly long enough. Before the French reclaimed it and Auteur became nothing more than another post modern band moniker. And by the way, that’s the pride of Daly City, DJ Rise on turntable. Rise and I have been chipping away at our own record for a while. Stay tuned.

God’s Arms

A story within a story, based on a line from a romance magazine. Reincarnation, shape-shifting, Bobby Gentry strings blowing in from the east. Buddy Holly on opium. Resurfacing on a rehab collection plate.

Diamond Jim

Who the hell is Diamond Jim? There’s a finders fee, but not a big one. I found a stack of 45’s at a flea market. Watt’s One Hundred and Tenth Street Rhythm Band, James Brown, Lowell Fulsom, Inez Foxx, Bull and the Matadors and the like. I added them to my swelling collection. I lived with them till they got under my skin and stayed there. I would’ve loved to have come up with a new post millennial dance step, but this is what came out the other end of the Cuisinart. Without Diamond Jim, the BBQ is just row after row of sizzling meat and the announcer wont say “play ball.” Diamond Jim is the patron saint of the Apocalypse. Until he comes back, traffic lights will blink incoherently. Fowls will fill the air, rivers will change directions, my laptop will go up in digital dust.

Bring it on.

I Couldn’t Be Happier

Here Comes the Bride? Having recently gotten hitched, I got to thinking someone should write a song for the grooms. Where lovers sway in the key of A minor. I never got around to finishing this song. The first time I ever sang it is the version you hear.

Lucky

Revenge is a dish best served cold. This guy steals your band and marries your girl and you end up running his sound board and taking her dog to the vet. We wrote it thinking it might be perfect for Johnny Cash. It turned into this, which might not be so perfect for Johnny Cash after all. Who wouldn’t like to get lucky?

Dyin’ All Young

Major 7th chords and a towel over the snare. Who’s gonna count the song off now?

Statehouse (Burning In the Rain)

Its bound to happen. Everything will. I play the patsy, the guy who just wandered by and took the fall. Farfisas provide the stabbing punctuation. Even the buildings built to last forever don’t. In Havana as elsewhere, sometimes people cheer for all the wrong reasons.

La Paloma

On the road again. California is so close to Mexico that whenever we mention it someone is sure to remind us we stole it. J.J. Cale locked in the research department of Mattel Toys.

April 30, 2002

A movie that never was

Songs were born around campfires and grew out off field hollers, at least according to Alan Lomax and other people who know such things. The birth of the album is another consideration entirely Many excuses have been offered. Megalomania even bought us the ‘theme’ album—sort of an evil twin to the ‘double’ album. (Hey, it worked for Pete Townsend.) Today still, the odd studio-glazed soul will look back on twelve virgin tracks and insist to anyone within earshot, “Shoot me if(this doesn’t tell a story”

Chuck Prophet

THE HURTING BUSINESS

(treatment for a movie-that-never-was)

1. Rise 2. The Hurting Business 3. Apology 4. Diamond Jim 5. It Won’t Be Long

6. Lucky 7. God’s Arms 8.1 Couldn’t Be Happier 9. Shore Patrol 10. Dyin’ All Young

11. Statehouse (Burning In The Rain) 12. La Paloma

The hero, an unknown who should favor Steve McQueen, is a modern drifter risen from the Lee Van Cleef western mist and remains nameless throughout. The closing credits identify~ him by only a Japanese ideogram [as the Man With No Computer].

In track 1, he has just been released from rehab and makes his way across Texas to ‘claim’ what is ‘his’. After a short honeymoon reunion, Re and She pick up where they left off, pitched battle in a rented room. They take and give pleasure freely, although the scales tip heavily towards disharmony.

In track 3, he reflects upon the chip on his shoulder, and everyone else’s and shakes his head, expecting it to fall off. Perhaps absorbing the premillenial heebie jeebies in the air, he seeks Salvation, in the vehicle of a local charismatic.

In track 5, he has become disillusioned with Diamond Jim. Nursing the mother of all relapse hangovers, he surveys his surroundings and prospects and laughable loves, and cries a dried-up creek. Next, he drinks anew, this time from sense of purpose.

In track 7, having abandoned his previous pursuits, he realizes he has become a stranger to himself, which plays right into his hands. He does things he is not ashamed of, but of which he will never tell another living soul. Unexpectedly, love enters the picture in a deep blue sea kind of way and he finds himself exchanging vows in front of a churchful of suits and dresses and Flowergirls and discovers he has parents.

In track 9, he partakes of the fruits of this life in Los Angeles itself [, and even acquires a used lap top]. Looking down from the Hollywood Hills, he soon

realizes his fellow travellers down life’s autobahn are falling all around him, whether the victim to their own criminal poses and an early check out time or to retro postures of respectability.

In track 11, disappointed, desperate mob take short-sighted satisfaction from sheer incendiary destruction of the very community and world they must breath in. Surprising himself, he does not join in, but makes tracks south to drink gallons of iced tea in Veracruz on the Mexican sand, from where he calls to try to begin to set things straight between them.

March 31, 2002

The Hurting Business

Ex-Green on Red mainstay Chuck Prophet continues his solo metamorphosis with The Hurting Business

Prophet comes clean: “Rock ‘n’ roll has just gotten too precious.”

The first thing you notice talking to Chuck Prophet, naturally, is his voice. Not so much the way it sounds—a raspy, unfettered bark—but the attitude it projects. His is the tone of a polite cynic—filled with gallows humor, self-deprecation and a world-weary indifference. The kind that seems logical given a lifetime of cult success and junkie excess.

The L.A.-born Prophet spent nearly a decade with ‘80s psychedelic cowboys turned roots avatars Green on Red, most of it riding shotgun with partner/singer Dan Stuart. By the time the group ground to a halt some nine years and 10 albums after it had begun, GOR had yielded a rabid underground following (especially in the U.K.), a vaunted critical legacy and little in terms of tangible success.

Meanwhile, Prophet had become the victim of the clichéd rock ‘n’ roll existence, plunged into the depths of a herculean heroin habit that left him at death’s door.

But by the mid-‘90s, life found Prophet clean, married and in the throes of a fruitful, if overlooked, solo career.

Terminally deadpan, the lanky guitarist brightens when discussing the genesis of his fifth and latest album, The Hurting Business—a radical and triumphant departure from the journeyman country-rock of his past.

The idea for the record was hatched after Prophet returned home from a lengthy tour in support of 1997’s Homemade Blood. In his mind, he had already conceived a loose-knit concept album which would take an aural shift away from the innately folkish charm and Exile-era Stones aphorisms that had marked his previous work.

“I had a sound in my head,” recalls Prophet. “And I wanted to take a cinematic approach with it.”

Prophet’s primary influence in creating The Hurting Business wasn’t musical, but rather inspired by Danish director Lars Von Trier’s “Dogma 95” film movement. Stylistically rooted in naturalism and realism, Von Trier’s pictures (most notably Breaking the Waves) focus on the vagaries of contemporary life, filmed without effects, using natural lighting and jarring movements provided by hand-held cameras.

To help him achieve a similarly original and vertiginous feel on wax, Prophet hooked up with Jacquire King, an engineer and desktop recording wizard who helped shape Tom Waits’ grim-and-grand weeper Mule Variations.

“Part of working with him was a desire to get out of the normal staid studio recording process. We just kind of took my original four-track sketches of the songs and loaded them into the computer and were able to go in and add and cut stuff wherever we wanted.”

Prophet also strove to match the organic feel of the Dogma style by capturing a natural ambiance on his vocal tracks, recording them everywhere from the front seat of his car to a bathroom stall. “I’ve never been one to require mood lighting or candles when I sing,” he notes with a chuckle. “But sometimes you do feel the need to extend the mike cable a little bit so you can get that same feeling you get when you’re sitting there singing by yourself.”

To complete his vision, Prophet decided he needed something more than the jagged guitar chords he’d long relied on. He found what he sought in the lexicon of electronic music—the stutters and starts of turntables and elasticized grooves of machine-made beats.

“That was definitely inspired by a lot of things I’ve been hearing,” says Prophet, rattling off a list of names that range from hip-hop eclectic Dr. Octagon to neo-blues experimentalist Jon Spencer.

“It’s at the point where people are taking traditional songwriting or traditional structures and figuring out ways to twist and turn them sideways. That’s always the fun part—kicking the song around and wrestling with it. Seeing how much you can beat it up beyond recognition before it gets worse.”

Much of Business is augmented by loops, scratching and the occasional sample—the bulk of them provided by prominent Bay Area turntablist DJ Rise. The album’s cut-and-paste fusion teems with an overall quality that mimics the laid-back jazz cool and foreboding sonic textures of Portishead and the Sneaker Pimps.

While the move may smack of an aging roots-rocker’s bid for postmodern relevancy, Prophet incorporates the subtle electronic touches so deftly, they seem less an intrusion or distraction than just another instrument at his disposal.

If anything, the songs lend themselves to such tinkering as Prophet’s effort comes off more memorably than Joe Strummer’s Rock, Art and the X-Ray Style, and more genuine than the Stones’ Bridges to Babylon flirtations with the Dust Brothers—both forays by traditional rockers into similar loop-and-sample territory.

But beyond modern accouterments, the foundation of The Hurting Business is rooted in a bedrock of deep soul sounds—black and white, North and South. Songs that draw on greasy R&B, from Muscle Shoals to Harlem, and a strain of late ‘60s country/pop that Prophet calls “housewife goth.” “Bobbie Gentry, Tom T. Hall, Dusty Springfield, Jimmy Webb—all the great story songs from that era.”

Consequently, there is a heavy emphasis on craft. Half the album’s 12 songs clock in at three minutes or less, a structure that Prophet regards as vital to the essence of his work.

“Rock ‘n’ roll has just gotten too precious. I hear records nowadays and the fades are like a minute. If you go back and listen to James Brown or Charles Wright, Betty Harris, Lee Dorsey, any of the stuff I was soaking in the couple years where I was working toward this record, they’re like two and a half minutes long—that’s it. And when they’re over, all you want to do is put the needle back to the beginning. That’s the kind of record I wanted to make.”

Prophet should take heart; The Hurting Business is exactly that kind of album, one that invites frequent and repeated listenings, yet provides new revelations with each spin.

Kicking off with the funky Ennio Morricone-influenced opener, “Rise” (“A change, a change is gonna come/Those very words once left me numb”), Prophet fashions a sometimes dark, often funny narrative of modern life, seething with urban tension, and sprinkled with caustic insights and pop culture references.

The title track, an insistent farfisa-maraca number that hints at Beck, were Mr. Hansen in the midst of a serious Sir Douglas Quintet jag. A he-did/she-did tale of fraught relationships and bruised romance (“You hurt me, baby, and I hurt you/Sometimes we fake, sometimes we jab/Sometimes we bounce right off the mat”), it takes its name from the unlikeliest of sources, a Mike Tyson quote.

“It was during a press conference after he bit off Evander Holyfield’s ear. They asked him if he wanted to apologize, if he felt any remorse about what he did. His reaction was just belligerent and insolent: ‘You understand, I’m in the hurting business, that’s my job,’” says Prophet in sotto voce, imitating Tyson. “He thought he was doing his job in there. I liked that. I don’t know how it relates to what boys and girls do to each other, but it ended up in my notebook.”

Prophet’s vocals—which normally split the difference between Tom Petty’s redneck whine and Kurt Wallinger’s British drone—take on a variety of hues here: the somber baritone of “Rise”“; the funky drawl of “Diamond Jim”“; the angelic croon of ‘Dyin’ All Young.”

On “It Won’t Be Long,” Prophet’s singing recalls Iggy Pop’s dry, craggy tone. Ironically, the song is a more successful stab at the kind of moody string atmospherics that the middle-aged Stooge attempted on last year’s career nadir, Avenue B.

The song’s theme, like much of Business, is imbued with a sense of irreverent topicality—in this case, it’s the world of the confrontational daytime talk show. “What we were trying to imagine was what the mother lode of all hangovers would be like if you stood naked on Jenny Jones and embarrassed yourself in front of a whole nation,” says Prophet, breaking into a coarse laugh. “What would the morning after that be like, when you realized what you’d actually done?”

Peter Anderson

Pills and booze: Prophet (left) and Stuart with Green on Red in 1989

While the subject matter may be bleak—Prophet characterizing it as “trailer park trash with high Arbitron ratings” and “the sad beauty of freak encounters recollected”—the song retains a light, almost absurdist lyrical quality: “I like T-Bone Walker/I like Wonder bread/I like to quote back in your face/All the things you never said.”

Elsewhere, Hammond organ colors the deathly revenge anthem “Lucky” (“I’d like to get Lucky/Get my fingers ‘round his throat”), its dark, smoky verses and skewed sonics surrendering to a chorus that arches up toward classic pop territory.

Not surprisingly, the record does stumble upon some of Tom Waits’ patented gruff ‘n’ clang, with the jagged blues and vocoder/megaphone intonations of “La Paloma” and the funky “Shore Patrol” (another vaguely Beck-ish sounding number).

At his best, Prophet seems capable of synthesizing his many influences—musical and lyrical—into a uniquely original vision. When he does, the results are the apogee of understated brilliance, as on the album’s centerpiece, “Apology.”

A languid mesh of warm bass and Mellotron, the song takes the universal human need for forgiveness and turns the concept on its ear with a litany of comical examples: “CBS from the MTV,” “the shoulder from the road,” “the Cancer from the Scorpio.”

But the moment that best captures Prophet’s ironic worldview comes after a verse in which he opines that “someday soon the Vatican is gonna call”—an allusion to the recent papal apology for the Catholic Church’s toleration of the Holocaust. Prophet follows that heady reference with a bridge that asks, “How can I swallow every little thing she says?/She don’t even know Elvis from El Vez.”

It’s the kind of uncommonly literate moment that bridges hard-edged romanticism and precise musical syntax, while plumbing the depths of pop arcana.

“When you start talking about when the Jews are going to get an apology form the Vatican, you can’t follow that up with anything too heavy,” says Prophet. “You gotta get into something as pathetic as falling out with a girl because she doesn’t know the difference between Elvis and El Vez. Some people, man, that’s how small their world is.”

Surprisingly, Prophet’s signature guitar work is downplayed on The Hurting Business. The album boasts few traditional solos, as the instrument is more a character actor than a featured star in Prophet’s wide-screen production. His twangy runs and subtle fills are still there, but they never rise above the songs, married instead to a bed of keyboard sounds, clipped percussion and ghostly background vocals (provided by a studio cast that includes Prophet’s wife, singer/pianist Stephanie Finch; bassists Roly Salley and Andy Stoller; American Music Club’s Tim Mooney; and longtime drummer Paul Revelli, among others). For Prophet—a man who made his early reputation as a six-string hot shot—the lack of over-the-top fretwork isn’t a problem.

“My tendency is to turn the guitars down. I hear that sometimes with Lindsey Buckingham or J.J. Cale—where it sounds like they’re just a little bit underneath everything. I don’t know why, that’s just where my sensibilities lie. It’s not that way onstage, though,” he says.

Like a number of his fellow roots-rockers, Prophet has long faced an unusual career quandary; all but ignored in his home country, he’s maintained a healthy following—even minor star status—overseas.

“I’ve got a love/hate relationship with Europe. I mean, I enjoy the success we have over there, but I’m not making this music thinking what someone in Paris would like. I’m making American music,” he offers adamantly. “After a while, you start walking around thinking you’re crazy because you’re not connecting with more Americans. But I think we’ve sort of turned that around with this record. It’s been really gratifying to go to shows and see a lot of people, especially when they speak English.”

Since its January release, The Hurting Business helped boost his profile in the U.S., earning the kind of breakthrough hosannas from critics that Prophet supporters have long demanded. Despite that, his sales remain modest, a situation that he feels will be remedied over time.

“The thing about being a solo artist is you tend to get discovered and rediscovered. I think the real challenge is building a nice body of work that people can tap into anywhere along the line.”

Prophet’s solo catalogue is impressive, running from 1990’s country quaint Brother Aldo, through the Cosmic American muse of 1993’s Balinese Dancer, continuing with 1995’s unassumingly retro Feast of Hearts and up to his previous long player, the suburbia study Homemade Blood.

Unfortunately, the bulk of those titles are hard to find on these shores. Only Business is readily available, and it was originally recorded for the U.K.‘s Cooking Vinyl label, only later to be licensed for American release by Hightone.

Still, Prophet’s popularity is flowering in many quarters, thanks in part to the cult surrounding Green on Red, one that continues to grow on both sides of the Atlantic. In 1995, China Records released a GOR best-of; in 1997, Germany’s Normal issued Archives Vol. 1, a retrospective collecting demos, B-sides and live tracks; in 1998, Edsel U.K. put out the group’s last four albums as a pair of special-edition two-fers. And later this year, Restless Records will issue an expanded, remastered version of 1985’s alt-country pioneering Gas, Food & Lodging.

Prophet (who hooked up with the originally Tucson-based Green on Red in L.A. in the mid-‘80s) looks back at his time with the group fondly. Still, he has no regrets about GOR’s 1992 demise.

“You can only drag your adolescence so far into your adulthood. Being in a band is like living with your parents. You gotta move out of the house before people start talking—‘How old is he? 35 years old and he’s still living at home!’” he says, amid gales of laughter. “It’s just natural to get out of it. Plus, nobody can break me up. I’ve tried. Believe me, I tried to break myself up and it’s hard to do.”

While the arc of his work clearly proves that Prophet has benefited from solitude, he hasn’t remained cloistered. On the contrary, he’s been an in-demand collaborator on projects ranging from alt-country sweetheart Kelly Willis’ 1999 comeback LP What I Deserve (Prophet plays on the album and co-wrote its “Got a Feeling for Ya” with Southern soul composer Dan Penn) as well as hired gun for alterna-rockers Cake and Hollywood songwriter cynic Warren Zevon.

“It’s always flattering when the phone rings,” says Prophet. “Sometimes you do it just to pay the utility bills and sometimes you get lucky and get to work with somebody like Kelly Willis out of the blue, and it ends up being really rewarding.”

Prophet also recently returned to the group fold, with an all-star contingent known as the Raisins in the Sun. Featuring legendary Memphis pianist/producer Jim Dickinson (Replacements, Big Star), knob-turning tandem Sean Slade and Paul Kolderie (Uncle Tupelo, Radiohead), singer/songwriter Jules Shear, and Dylan rhythm foils Harvey Brooks and Winston Watson, the group convened in a Tucson recording studio for two weeks in May 1999, with the notion of writing and recording an album from scratch.

“That was a leap of faith for everybody,” says Prophet of the sessions. “I think we were all prepared to go down to Tucson and come away with nothing.”

Instead, the collective came away with a self-described “10 slices of rock and soul” that are tentatively scheduled for release on Rounder Records.

Prophet’s immediate plans include the long-delayed completion of the debut album from Go-Go Market, a collaboration with wife Finch that he describes as “fulfilling a Brill Building jones.”

A follow-up to Business is also in its early stages. Instead of again taking the redacted studio route, Prophet plans to write and record a more ornate and traditional album, one that will feature fleshed-out arrangements, horns and a string section.

It’s hard not to marvel at Prophet’s versatility and output. It seems especially remarkable for a man once regarded as the epitome of wasted, junkie cool. The same Chuck Prophet who once denounced “rehab” as artistic immolation on the pages of Melody Maker.

“In a lot of ways I feel like I’m crazier now than I was back then—I’m just not on drugs anymore,” he says, laughing. “I’m off my medication and I feel like I’m much more dangerous now. I really do.”

by

Bob Mehr

on

February 28, 2002

THE TAPE HISS INTERVIEWS

[The following interviews are transcribed from John Sekerka’s radio show, Tape Hiss, which runs on CHUO FM in Ottawa, Canada. Each month, Cosmik Debris will present a pair of Tape Hiss interviews. This month, we’re proud to present an interview with Chuck Prophet, formerly of Green On Red, and from the Tape Hiss vaults, a 1992 interview with the tragically under-heard instrumental band, Pell Mell.]

CHUCK PROPHET

Green On Red were one of the ground breaking pioneers of cow punk, the thing that’s all the rage nowadays with bands like Sun Volt and Wilco. A band born a decade too early, they managed to lay down some criminally overlooked albums. Guitarist Chuck Prophet has emerged from the ashes with a nice collection of solo recordings, culminating in this year’s earthy “Homemade Blood”. From a San Francisco studio , Chuck talked about the old days, the new days, LSD trips, suburbia and dealing with the dictatorial producer, Steve Berlin. We also had an argument over a classic album.

JOHN: What’re you working on?

CHUCK: I’m just putzing around. I have to go to the studio and pay people to hang out with me. My lifestyle: friends and making records are all intertwined.

JOHN: Are you a musician seven days a week, twenty-four hours a day?

CHUCK: Yeah, but I don’t take it to bed. It could change any day. I could be down on Montgomery Street at six in the morning trying to sell flowers. I’ve thought about it.

JOHN: Let’s get to it: I quite like your new record, Homemade Blood. Compared to Brother Aldo, which was a more gentle, countrified album, it sounds like you just wanted to rock out.

CHUCK: Oh sure, sure. I was less interested in the process of making a record. I just wanted to get five people together, keep it simple, kicking the songs around, and trying to stick ‘em to tape with as little fuss as possible. You can hear people talking to each other on the record. The last record I made was with Steve Berlin [Los Lobos], and it was a bit involved. He couldn’t resist the temptation to put his fingerprints on anything and everything. He was running around with a flashlight, looking at what he could tweak. I just got a little tired of the process, you know? I like to ride. I like to get up and do something creative every day, and I wanted this record to be more of a live situation. Not that there wasn’t a lot of blood on the floor after I beat up the songs.

JOHN: I hear ya. It sounds like you got a little dirty. The press likes to pigeonhole you with a Rolling Stones sound, but what I hear is a bit of Tom Petty and The Replacements. Do labels offend you?

CHUCK: Naw, I also bear a resemblance to Tom Petty. I blame my parents. I don’t mind. The Stones, The Replacements - they’re just taking traditional stuff that’s laying around and turning it sideways. And that’s pretty much what I’ve always done.

JOHN: Do you know when you’ve nicked a riff, or does it sometimes come to you later?

CHUCK: Ah, I just ignore it and hope it goes away. I heard Keith Richards once held up an album for two months cuz he thought it [the nick] was gonna come to him. I used to pole vault over those mouse turds, but now I just walk through ‘em. I don’t care. By the time you beat up a song, take it through changes, if it’s still living and breathing by the time you stick it to tape, usually it’ll just go away. The initial riff or whatever it was that sparked the place in the back of your mind that made you think of sitting in the car with your Mom listening to Glenn Campell. They just go. It’s something in the subconscious editing process.

JOHN: How often do you write songs? Do they come to you, or do you tinker in the studio until something evolves?

CHUCK: I collect stuff, and every once in a while I’m lucky enough to get up in the morning and pull one out from the roots. Sometimes I gotta drag someone along. I do a lot of co-writing. Other times, I’ve written out of necessity, but those are never that good.

JOHN: Is there a difference making music in L.A. [Gun Club] and making music in San Francisco?

CHUCK: There’s music in the air in L.A., and I grew up in a time where music was coming from every car. It was everywhere. I took that for granted. I dunno if you get that everywhere. Living in San Francisco now - there’s an artistic thing in the air here that’s left over. It’s kinda cool. I don’t think they would have put up with The Grateful Dead in L.A. Some people say music’s all about geography - Jim Dickinson says the reason that the grooves are so sticky and greasy in Memphis is because the air just hangs heavier, all that humidity. There might be some truth to all that stuff.

JOHN: Dickinson produced Green On Red didn’t he?

CHUCK: Yeah, he’s the guru of voodoo. I’ve seen him do so many things that were invisible, just by being in the room. He’s a real presence. We did a live recording together in ‘94 which was bootlegged and is now on a French label.

JOHN: What label is that?

CHUCK: Last Call. It’s run by a fella who used to run New Rose, which was famous for putting out records by people who were dead, half dead, on the way up or on the way down.

JOHN: A great label. What is the official status of Green on Red anyway?

CHUCK: I dunno. We broke up every six months. We like to say that we went on strike. We’re still entertaining offers.

JOHN: So you keep in touch with Danny Stuart?

CHUCK: Yeah, I talk to him occasionally. He might leave a cryptic message on my machine recommending some conspiracy book or another.

JOHN: Can you reveal who wrote what in Green On Red?

CHUCK: Most of the time Danny carried away the writing. I might bring in something, a riff with words attached and we would run with it. Sometimes I’d bring in something that was completely finished.

JOHN: So this lyrical side of you is a new thing?

CHUCK: Naw, I’ve always written songs. You know writing with Danny was great. He’s fearless. He’d put a lot of things in songs that normally wouldn’t be in songs. He had a song about a guy with an enormous foot who made his living traveling in a minstrel show.

JOHN: I’m a big fan of Green On Red, especially “The Killer Inside Me” record.

CHUCK: Well you’re the only person who liked that record. We thought that it was just miserable.

JOHN: I’ve read that. Why do you think it miserable?

CHUCK: Well it was miserable making it. We thought that we were so bad-ass, so reactionary, and Danny had so much anti-establishment rhetoric. When we tried to make a record that actually rocked, we couldn’t rock to save our lives. I don’t know what it was. We were trying to make a ZZ Top record or something. It was like the Kingston Trio trying to jam with Robert Palmer. It just didn’t work. It was really bombastic, cold and overblown, and underneath it all were these tired, lackluster performances.

JOHN: But I love that record!

CHUCK: Maybe that’s what makes it exciting, but I don’t wanna listen to it.

JOHN: Really? The lead off track, “Clarksville,” is a total killer.

CHUCK: Yeah? Maybe we should stop apologizing and start a rumour that it’s a masterpiece… [pause] ...That record is a MASTERPIECE!

JOHN: Now you’ve got it. Were you guys fighting in the studio at the time?

CHUCK: Nobody cared enough to get that upset. We cut way too much stuff. Half of it had a sense of humour, it was kinda playful, and the other half was pretty bombastic. There were two records in there, and they were fighting each other.

JOHN: You know the CD version also has the No Free Lunch EP on it, so there are THREE records fighting it out!

CHUCK: There’s also an Australian bootleg which we authorized, that has all the outtakes. So if you’re such a sucker for punishment…

JOHN: Why go from Green On Red to solo work?

CHUCK: Well, I kept writing and playing outta necessity, outta habit. Luckily there was this bar called The Albion at the end of my street, and we could take it over on Friday and Saturday nights. These songs just appeared, and I thought I should get ‘em outta my head and on tape. I thought I was outta the music business. I was twenty-four years old, and I figured I got my shot. I was naive, thinking that cassette would be publishing demos. The tape got into the hands of some dude in England who decided it would make a record, and that’s what Brother Aldo was.

JOHN: Green On Red was always more popular with the British press. Is that still the case?

CHUCK: I suppose. We just spent more time over there cuz we got signed to a British label in ‘86 or something. They only see so far in front of their faces, so we ended up on the cover of Melody Maker and Sounds. By the time we were done over there, we were too tired to work back here.

JOHN: That was a great time for cow punk, back in L.A. with you, The Gun Club, The Dream Syndicate, X ... Was that a close knit community?

CHUCK: We crossed paths, though we never shared a house or anything.

JOHN: Do you carry a guitar with you at all times?

CHUCK: Naw, not really. A friend of mine is like that though. He was doing sixty days in county jail, so he made a guitar outta cardboard to keep him company.

JOHN: How would he play it?

CHUCK: He just moved his hands, knowing how it would sound. I’m thinking of making one - my neighbours would love it.

JOHN: Do you get written up and fawned over by guitar magazines?

CHUCK: Yeah, I get the obligatory piece with every record.

JOHN: How do you find that almost geeky worship? Is that a bit embarrassing?

CHUCK: It’s kinda fun, cuz the rest of pop culture has become too intellectual. It’s great to talk about Russian guitar pedals for a change.

JOHN: For all the guitar geeks out there, could you outline your latest gizmo?

CHUCK: Well, I’m really into this thing called an envelope follower. It plays whatever you’re playing an octave lower, and if you hit it harder - it’s touch sensitive - it bubbles like lava up an octave. It’s really painful.

JOHN: Painful to hear or to play?

CHUCK: Painful for everybody in the room - when it explodes. It’s really cool.

JOHN: Let’s get back to the new record. On the very catchy “Ooh Wee,” you mention being strung out on ritalin and colour TV at nine years old.

CHUCK: Wasn’t everybody?

JOHN: Damn right. Growing up in L.A. in the early seventies must have been pretty wild.

CHUCK: I was lucky enough to have an older sister who got into a lot of trouble.

JOHN: Were all your experiences second hand then, or did you find trouble yourself?

CHUCK: We don’t have that kinda time.

JOHN: We don’t? You must have one story you can sneak in here.

CHUCK: I was arrested and thrown in jail, peaking on two hits of LSD. But the story itself is kinda boring unless you were there. There is a moral, though: you gotta fix those parking brakes and things, else you get pulled over.

JOHN: Listening to “Homemade Blood” I get a feeling that you write about mid-America - some might call it suburban white trash - not condescendingly, more as an observation of the lifestyle.

CHUCK: The last couple of records were influenced by my immediate surroundings. Certain events led me back to living with my folks in the suburbs. There’s a photographer, Bill Owens, who took pictures of suburbia developments in the seventies. I saw his pictures in a museum and I got into that. And when I got back home everything had changed. The Dairy Queen was gone. I found myself bumping into ghosts, and some ended up in my songs.

by

John Sekerka

on

January 1, 2002

Westworld

The Hurting Business

Chuck Prophet’s earlier solo work was likable enough: twangy, stripped-down roots rock that, released nowadays, would immediately get him pegged as yet one more exponent of alternative country, singer-songwriter division.(Think Tom Petty without the Byrds infatuation and recording budget.) The Hurting Business, though, rises head and torso above his four previous albums and includes Prophet’s best work since his days as a kid guitar-slinger for the too-soon-gone Los Angeles band Green on Red.

The superiority of The Hurting Business can mostly be attributed to a shift in direction, away from Prophet’s previous roots-rock recordings—in the whitest sense of that term—back to the broader conception of roots exhibited by Green on Red’s best music, a vision that embraced not just the Stones and Hank Williams, but gospel, blues and soul, as well. With The Hurting Business, Prophet puts these R&B roots in the foreground by making sure that his evocative lyrics ride a groove; he then modernizes them with distressed turntable beats and looping DJ samples. Prophet isn’t the first former folkie to get funky lately, but he stakes out his own territory. The Hurting Business is catchier and more accessible than similar recent recordings by Joe Henry and more traditionally song-driven than most Beck.

Prophet’s rediscovered soul provides a fitting soundscape for the album’s corrosive sense of loss. A family beset by a tragedy of its own device finds itself on the local news, then abandoned—“in rags, with a summer to kill”—when its fifteen minutes are up; a loser wants to get lucky, and then we realize that Lucky’s the guy who stole his girl [“Lucky” 237K aiff]; a man leaves us wondering if “I couldn’t be happier” [“I Couldn’t Be Happier” 248K aiff] isn’t just about the most depressing thing someone could possibly say. Most powerful is “Dyin’ All Young [267K aiff],” in which Prophet’s newfound grooves console a grieving mother even as they push her to tears.

by

David Cantwell

on

February 9, 2000

USA Today

No Other Love

Chuck Prophet is a real find, an innovative genre-fusing talent with a wry sense of humor and fearless approach to musical alchemy (especially in mixing alt-country and hip-hop—whoa). His new album, No Other Love, is even better than 2000’s The Hurting Business. I strongly recommend both. I hope his indefinable sound doesn’t relegate him to the radio wastelands. He deserves exposure and recognition.

by

Edna Gundersen

on

December 31, 1999

Homemade Blood

You won’t find “homemade blood” in the dictionary, or in any lab manuals. But with the release of Chuck Prophet’s Homemade Blood, look for the term to show up in the next editions. “It was a song first,” explains Prophet. “I guess the words somehow floated to the top of the pool. I just like the way they sound, kinda plain. Plus at the same time, maybe something’s going on underneath. Life and people are like that anyway.”

Homemade Blood is Prophet’s fourth album, his first for Cooking Vinyl, which is issuing it simultaneously in Europe, where he enjoys a semi-respectable cult following, and in the US, where the tangled relationship with his former label kept his last record (Feast of Hearts) from being released Stateside.

It was recorded in ten whambam days last Fall at San Francisco’s venerable Toast Studios with producer Eric Westfall (Giant Sand, Sidewinders), and mixed at Ft. Apache by Boston-based console wizards Paul Kolderie and Sean Slade (Dinosaur Jr., Morphine, Hole, Radiohead) in an equally improb-able 72 hours. Hardly the prepackaged stuff of contemporary record making. But then, Prophet’s rarely gone with the conventional wisdom. Prophet says, “The only way I ever got anything done was to slip through the side door when nobody was looking. Right now I don’t have the patience for this whole ‘Orson Welles with a home video camera’ process that’s going on in pop music today. I’ve seen people drown in that process.” Applying that attitude to the making of Homemade Blood, Prophet cut it live: Warts, happy accidents and all. Capturing what he calls “those ‘conversational’ things” that find their way into music when people are playing together live and reacting to one another. “It takes a lot of work to set up live and get five musicians on tape simultaneously,” Prophet admits. “But recording is such an elusive thing anyway. It always comes back to capturing that energy and spirit in the room at that time, you know?”

As for Homemade Blood’s whirlwind mixing marathon, Kolderie and Slade were going through a stack of tapes when they came upon Prophet’s. After listening to it, they got on the phone. “‘How about we mix the record? When can Chuck fly out?’ is what they said to my manager,” recalls Prophet with a laugh, “so I flew out to Boston where we managed to fly well under the radar of normal industry demands. “I think I said to them, ‘Hey guys, we’ve only got three days to do this, but don’t let that keep you from breaking out your Buzzbin-voodoo-fairy dust!’”

The twelve songs on Homemade Blood all go to lyric or sonic extremes—usually both. From the infectious, swaggering kickoff, “Credit” (“Get your hands out of my pockets/ You’re not my Uncle Sam”); through the minor-key lovers’ apocalypse title track (“You’ve got seven scarlet veils/ I’ve got a hammer and I’ve got nails…Pretty soon I’ll be fallin’/ I can hear my own voice callin’/ Drowning in a sea of homemade blood”); to the half-time pulp spiritual, “The Parting Song,” that closes out the album (“Sailor won’t you take me to the shore now/ Let me drink my fill/ Lyin’ down it feels just like a chore now/ Dyin’ ain’t no big deal”); Prophet’s in the driver’s seat on ride after ride.

He takes you to musical terrain at once familiar and unsettling, haunting and haunted. Along the way, you encounter characters exiled to suburban gothic cul-de sacs crammed with condos, mini-malls, and flophouses, and souls trapped in the black vinyl grooves of Neil Young’s Tonight’s the Night attempting to serve up chunks of desperate wisdom and sodden humor. “Tonight’s The Night? I can only aspire to something like that,” confesses Prophet. “I came from a real nowhere place, and when events forced me back, I had to deal with all that boredom and creepiness that drove me away in the first place. I found myself bumping into a lot of ghosts out there. I guess those ghosts eventually found their way into the songs.” Having spent the better portion of two years collecting songs, Prophet had nearly 100 to choose from, (“Well, they weren’t all finished”) when it came time to record. “I wrote by myself, with my friend Kurt, some well-known misfits and even an unknown celebrity or two. Twelve songs found their way onto the album. The worst of the rest, I think I got rid of the cassettes as blanks at a garage sale.” During that time, Prophet and his band—Max Butler (guitars, mandolin, pedal steel), Anders Rundblad (bass), Paul Revelli (drums) and Stephanie Finch (keyboards, accordion, vocals)—also did hit and run tours of the US and Europe, resulting in the group telepathy that ultimately made the unique recording circumstances of Homemade Blood possible. “Kicking songs around onstage every night is like taking your kid out in the backyard every afternoon and hitting grounders to him,” is Prophet’s proud summary, who further brags that “this band is the best one I’ve ever had in any price range. So far I’ve kept them all merely with my charm school style and a batch of IOU’s I print up down at Kinko’s.”

December 31, 1999

Interview with Chuck for the reissue of Brother Aldo

Hey chuck, how are you? how’s life in San Francisco? it’s cold and rainy in London. How do you feel about brother aldo being re-issued after 8 years?

It always nice to know your records are in print. I don’t have children but, after a while I imagine these records become like kids from another marriage. You don’t need to see ‘em everyday. One just takes comfort in knowing they’re out there fending for themselves.

What are your thoughts and recollections on the album?

Brother Aldo started out as song demos. At the time, I naively thought I might go to Nashville and get a gig as a songwriter. I was in a band (Green On Red) that had disintegrated (shortly after, resurrected-but that’s another story). I was ready to retire or head for the hills. I didn’t get the staff songwriter gig, but the cassette was dubbed here and there and when Chris Carr played it for Fire records head honcho Clive Solomon, he demanded to put it out. I made peace with my nasally nicotine stained baritone and we threw it out there. A modest but proud group of people responded and I’ve been making Chuck Prophet records ever since. And last year I eventually made the first of many treks out to Nashville to write.

Was there anything different about the recording process that went in to defining the sound of the record?

Producer/raconteur (sp?) Scott Mathew’s had converted his Bernal Hights shack into a makeshift studio. He had a funky AM radio console and one good German mic (which we used on EVERYTHING). In order to disguise some of the tape hiss we kept an old tube radio bleeding into the room at all times tuned in between the just the right two stations for the optimum static. This approach was later affectionately, commonly, referred to as “Lo Fi”. It was mixed as we went along on 7” inch 1/4’ reels which I carried it around in my suitcase. The tapes went through a couple airport x-rays machines before I made the hand-off to the Fire Record brass in a Camden pub. Which had me concerned for the first four pints or so.

How do you feel does it stand up to the test of time?

If I stand back and squint when I listen to it, I dare say it sounds timeless. I think because of a combination of the technical limitations and the spirit in which it was recorded, it’s held up. Thankfully, there was no one around who felt compelled to meddle with it too much . We didn’t bow to any of the conventional wisdom’s of the era; None of the bells and whistles that were goin around at the time, no boxed Japanese reverbs or effects to speak of. The real test is that when I kick some of those songs around on the bandstand (which I often do) they still manage to stand up for themselves.

What kind of music were you into at the time?

As I recall, whenever in doubt, I’d turn out the lights and listen to Waylon Jennings’ Dreaming My Dreams for inspiration. Certain records have the sound that they were made when no one was looking. LX Chiltons’ Flys on Sherbert , Neil’s’ Tonight’s the Night or the Basement Tapes come to mind. I don’t mean to put myself next to those records but on a good day I like think of Brother Aldo as a kind of kindred spirit.

Who is brother aldo?

He’s a character in one of the songs. I like albums that have names. Tim by the Replacements comes to mind. I’m sure there’s others…

How did you feel about working with that many people on brother aldo?

It was mainly me and Stephie with Scott and Roly Sally together with whoever was hanging around at the time. One night we went to see JJ Cale. After the show we abducted Spooner Oldham and brought him to the studio to play piano.

As an artist what has changed for you in those 8 years?

Not a whole lot. Back then I carried those songs around in my head or backed up in a compositional note book. Now I have a laptop that saves everything. And when the song Gods are smiling it comes out of my fingers straight into the hard drive. If anything’s changed, we all like to think we get better. I Guess I’m no exception. I like to think I’ve learned and unlearned some things along the way

What’s it like working so closely with your wife Stephanie?

Nobody can sing around me like Stephie. It’ been known to get a little crazed but , hey , what am I gonna do? At this point she knows where all the bodies are buried.

What are your plans for the future? And what can we expect from the new album you’re working on at the moment?

The plan is to keep my self entertained. Any day now I’ll assemble the usual cast of Mission district musicians and characters to the studio. Maybe return to FT Apahe under the watchful eyes of Sean and Paul. We might augment it by cutting some tracks with Dan “The automator” AKA Dr. Octagon. With one eye on Hip Hop culture and one eye for wreckage in the rear view mirror. We’ll heat up the BBQ till the coals glow in the dark; Tear a couple pages from the blood stained diary and throw em in there. Then we’ll wrestle with the songs straight to tape, before they get too housebroken. and serve ‘em up greasy. You can expect less introspection, more visceral, butt shaking, sweaty revival music that I’ve only hinted at in the past. With a little luck it’ll be more in your face or up your nose.

How do you feel about the burgeoning No Depression scene in America and your place in it?

If they’re’ gonna have chat groups or rooms that debate over the best version of Townes Van Zant’s “Pancho and Lefty” how can anyone complain? Nobody invented that stuff. Anybody will tell you that.. But along with the new groups, it keeps people aware of the sources and the complete heaviness of artists like the Stanley Brothers and Furry Lewis. I dig it.

December 31, 1997

Buyers Guide

You can hear the strain of triumph ringing in every line, note and breath. Monster stuff!!

November 15, 1997

Q

Passionately ramshackle weavings on suburbia, lost love, life and death and the great beyond. Blistered Tele strangling amidst wah wah noodlings…like a man with a capo on his heart

November 15, 1997

November 15, 1997

All Music Guide

With Homemade Blood, guitarist and singer/songwriter Chuck Prophet created one of his finest achievements. The songs were inspired by a series of semi-autobiographical stories of growing up in suburbia only to enroll in the school of hard knocks and come out a fighter; it’s simultaneously cynical and reverent. The band that backs Prophet’s fiery guitar work is a roots rock unit tightened up from ceaseless European touring, and this live-in-the-studio recording suits their take-no-prisoners delivery. This record ought to bring Prophet some well-deserved kudos.

by

Denise Sullivan

on

November 15, 1997

BAM Magazine

Homemade Prophet

Chuck Prophet is literally livin’ large, so we arrange to meet for coffee with one caveat: “It’s got to be the right place, because I take up a lot of space,” he said. That’s ok. The guy has plenty to shout about.

His fourth solo album, “Homemade Blood,” shows off his stunning songwriting, guitar playing and vocals—a traditional, rootsy, raw, and heartfelt stew that digs for the source but comes out “sideways.” He has a new label, Cooking Vinyl and he’s been to Europe twice since the first of the year; he’s off again this Summer for four European festivals and a U.S. tour with his mighty band—Max Butler; guitars, Anders Rundblad; bass, Paul Revelli; drums and Stephanie Finch; keyboards and vocals. He just saw the release of a live collaboration with buddy and Memphis music legend Jim Dickinson and he remains happily ensconced in his San Francisco digs with his band mate and partner, Finch.

Though his struggle with hard drugs could make a case for the contrary, nonetheless, Prophet appears to finally be comfortable in his own skin. He looks like rock and roll personified—tall and thin, hair that looks like it’s never been washed, a cigarette dangling from his lips—the kind of musician they don’t make too many of these days.