BAM Magazine

Homemade Prophet

Chuck Prophet is literally livin’ large, so we arrange to meet for coffee with one caveat: “It’s got to be the right place, because I take up a lot of space,” he said. That’s ok. The guy has plenty to shout about.

His fourth solo album, “Homemade Blood,” shows off his stunning songwriting, guitar playing and vocals—a traditional, rootsy, raw, and heartfelt stew that digs for the source but comes out “sideways.” He has a new label, Cooking Vinyl and he’s been to Europe twice since the first of the year; he’s off again this Summer for four European festivals and a U.S. tour with his mighty band—Max Butler; guitars, Anders Rundblad; bass, Paul Revelli; drums and Stephanie Finch; keyboards and vocals. He just saw the release of a live collaboration with buddy and Memphis music legend Jim Dickinson and he remains happily ensconced in his San Francisco digs with his band mate and partner, Finch.

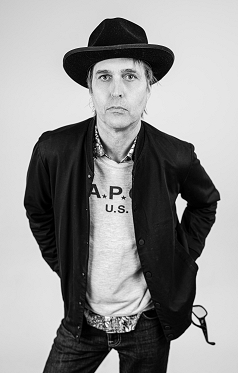

Though his struggle with hard drugs could make a case for the contrary, nonetheless, Prophet appears to finally be comfortable in his own skin. He looks like rock and roll personified—tall and thin, hair that looks like it’s never been washed, a cigarette dangling from his lips—the kind of musician they don’t make too many of these days.

Eleven years is a long time for anybody to sustain the kind of musical career Prophet has (without ever holding a day job), particularly when one’s music supersedes trends. His lyrics will often fuse the honesty and artfulness of Bob Dylan with the tunefulness of say, Tom Petty. For more contemporary references, you could pigeonhole him in the same place Pete Droge, the Jayhawks and Wilco reside (Americana/No Depression-land), but that would be doing Prophet a big disservice as belongs in a class by himself. He was simply born at the wrong time.

Had he been born earlier, his keen sense of rock history, his continual search for “the source” probably would’ve earned him the accolades of an Eric Clapton or Keith Richards. Had he been born later, he would be as lauded and adept at deconstructing rock as Beck. But Prophet belongs to that middle generation who live in the shadow of boomer musicians and fans and precede X-ers who don’t always care much about the source.

“I feel like Rip Van Winkle. I got way too many miles on me, man,” he said. “I wish I had a generation. I would’ve made a great slacker, but I’m just a little bit old and I wanted to do things,” he said.

His song “You’ve Been Gone,” from the new record perfectly explains that kind of lost weekend lifetime of experience: You’ve been gone, you’ve been gone, clouds make rain and days make years…I think you’ll find some changes here.

“The line, Sweet Lorraine’s on SSI, her mind walked off before she said goodbye made me think of all my drinking buddies at the Albion,” he said, referring to a 16th Street watering hole. “All of those guys were on SSI. I swear it’s gotta be more work than working, but I wouldn’t know.” Somehow, time slips away.

With the songs presented in a down-home style with none of the artifice that is currently fashionable (i.e. the lamest band on the charts that uses mandolin and accordion you can think of inserted here), since his days as the teenage guitarist in LA’s Green on Red, commercial enthusiasm for Prophet has never reached critical mass. But he’s a survivor and possesses a certain wisdom well beyond someone of his 30 some-odd years.

“Part of being real is what you learn from good literature, like Raymond Carver poems. They’re really plain and the way people talk is really plain and it’s so plain it hurts because it’s not glamorous. If you get real you get closer to the truth and if you get closer to the truth you get closer to God and that’s art. If there’s a just God, those people who are pretending are going to get busted anyway,” he said.

Funny that a man who looks to rock’s poet laureate, Dylan, as king songwriter would be espousing the pleasures of plain.

“Most of Dylan’s greatest songs are painfully plain,” he asserts. “Even though ‘In the Garden’s got the most complicated chord structure I can think of, it’s really a straightforward song as is ‘Knockin’ on Heaven’s Door’. You know what he’s talking about. Anybody can tie a bunch of lines together, but if you know where you’re going with it, then it’s a lot harder.”

“I could’ve dressed up the songs on the album in all kinds of gothic shit, and I didn’t. People don’t need to come to me for that,” he stated matter of factly. “You can’t find a source for this music. It comes from some guy strumming a fence on barbed wire. The Stones took traditional music and turned it sideways and that’s what I’m trying to do,” he explained.

Prophet’s “plain” songs for his fourth solo album were inspired by a detox-break he took last year at his parents suburban East Bay home, while he weaned himself “from sucking the glass dick,” as he refers to the crack pipe.

“I went back home and I realized it was the last place I’d been before I was kind of fucked up and I could smell everything and it was weird and brand new and kind of spooky. That’s where I wrote ‘K-Mart Family Portrait.’ I know exactly what happened. It has a Linda Ronstadt melody from her album, ‘Mad Love,’ that my sister used to have. I got kind of inspired because I got kind of creeped out. I don’t really get that when I walk up and down 16th Street anymore. I’ve strip-mined the Mission. There’s nothing there,” he explained. “And all the rural stuff has been strip-mined too—don’t go there.

Consequently, the album’s deepest vein is that of suburban angst. “I started having dreams about being a kid,” said Prophet. “I’m not precious enough to write my dreams down and think I’m going to turn them into songs, but there was a lot floating around. It was new subject matter to stick into songs—I wanted to stay off the known roads.”

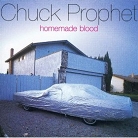

” My favorite Raymond Carver poem is the one where he’s sitting in his driveway in his station wagon drinking a six-pack and he can’t go inside because his family’s in there,” no doubt explaining the car parked in front of the pick-a-suburb home that adorns the album’s cover. When he finished writing, Prophet took his band into the studio to cut the songs live, to give the record the kind of free-wheeling feel that the group has developed as a consistent live act.

“Everything was a reaction to spending too much time in the control room on the last record. I wanted to have some fun with the songs and break out of the singer/songwriter mold.”

Prophet has kept the same line-up for some time which allowed the band to roll with the free-form and immediate recording process.

“I wouldn’t have done it like this if I didn’t have a band. Stephanie can sing around me which isn’t easy to do, but I never had a guitar player till I found Max. If it gets too comfortable, it’s not good, but when we’re on the road, we have these telepathic workouts. He knows when I bend over it means to do this—we don’t have to talk about it.”

As for living with a band mate, “it’s weird. You don’t really want to show anybody a song till it’s done. I got up one night to go to the bathroom and I went and picked up my guitar and Stephanie was yelling, ‘What are ya doin’ in there?’ and I was whispering a song into a tape recorder. I yelled back, ‘I’m writin’ a song.’ When I’m just pulling things out of the air, I don’t want anyone around.”

“Credit” is one of those fantastic songs that came out of the air while Prophet and one of his co-writers, Kurt Lipschutz, were working together. “It’s one of those character songs and a play on words. A song like ‘My Generation’ doesn’t look very good on paper but when he stutters it means so much more. Or like ‘Unsatisfied” by Paul Westerberg when he screams—it means so much. When my friend Kurt and I printed it out and it didn’t look that good, we thought, we’re really on to something now,” he laughed. “And I get to scream in it,” said Prophet referring to the line, “I want some CREDIT.”

“Someone in my manager’s office said, ‘That’s a good double entendre and my manger said, ‘It’s a single!’

Prophet doesn’t really look for outside projects, but often they(itals) find him(itals). He just played guitar on a little-known singer/songwriter, Calvin Russell’s new album.

“He used to walk about ten steps behind Townes Van Zandt,” he said. It was produced by Dickinson and features the legendary Muscle Shoals rhythm section. “It’s a top 30 album in France, as we speak. And I got to record in Memphis with Dickinson, and that was great.” Last year, he recorded with another songwriter’s sidekick, Dylan’s old pal, Bobby Neuwirth. Prophet spoke of the thrill of recording with yet another legend.

“There were eight guitar players in the room… Steven Soles, Billy Swan, Neuwirth, Rosie Flores…we did a run down of the song and I wasn’t sure who was going to play guitar and Swan said, ‘you take the lead,’ and I got to play my Telecaster with Billy Swan playing rhythm guitar. He played rhythm guitar for Kristofferson, you know?”

He also recently recorded with beat poet Herbert Hunke. “He’s dead now, so no one else is going to get to do that. I’m not the biggest Chuck Prophet fan, so I don’t have 50 side projects where I think everything I touch should be released. I do a lot of things and most of them are invisible and they probably just should be.”

“I’d still like to do a record with Stephanie, but we move at our own tempo,” he said.

Though he may have profited more had been born alongside his spiritual mentors—Dylan, Petty, Springsteen, Young, Dickinson, Van Zandt, Kristofferson, Neuwirth, Chilton and the like, Prophet won’t back down. Plus, he’s already made a couple of marks on the pages of rock history.

“I survived the Paisley Underground—now that was dumb. Some journalist was trying to get me to dis the No Depression movement—I wouldn’t, as long as we understand they didn’t invent it. I actually think Uncle Tupelo were pretty good and I like Wilco,” he said cheerily.

“I’m not nostalgic and I don’t think things used to be better. I think these are the good old days. “

by

Denise Sullivan

on

April 18, 1997

3_238_159auto_s_c1.jpeg)